|

Published on Edutopia www.edutopia.org/article/bump-it-walls-make-learning-progress-visible

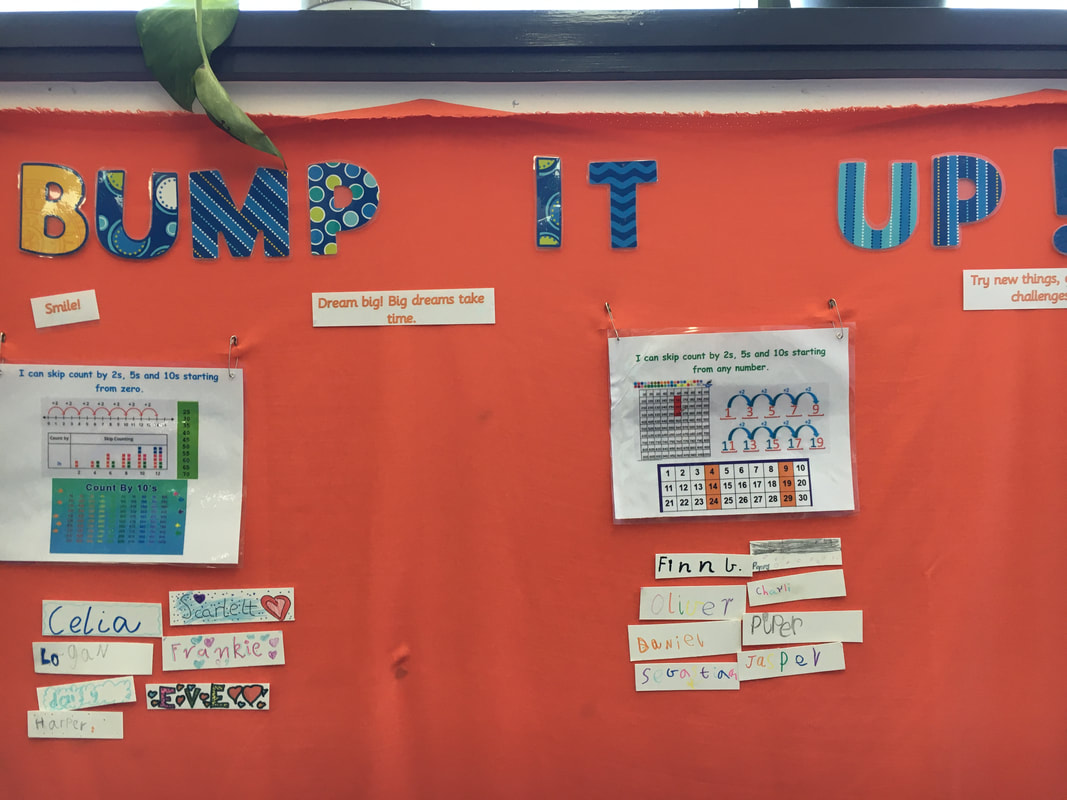

14/5/22 Bump-It-Up Walls Make Learning Progress VisibleTeachers can use this visual rubric to help elementary students reflect on and evaluate their own learning as they move through the curriculum. A good teacher uses formative assessment data to improve their teaching and address student learning needs. Isn’t it time we let our pupils in on the secret too? Bump-it-up walls are linear visual rubrics that clearly show students how they can progress in their learning. The walls can be used for any subject and work best when they are narrow and specific. Model work samples are displayed with annotations in a progressive continuum. Through formative assessments and student-teacher conferences, students learn to be reflective and evaluate their own learning. BUMP-IT-UP WALLS AS FORMATIVE ASSESSMENT TOOLSEducation researcher Dylan Wiliam explains that for formative assessment to be effective, students should have a clear and visible understanding of their learning target, the assessment should relate directly to future instruction, and teachers and students should review success and progress together. A bump-it-up wall accomplishes all of these goals, while also promoting student agency. Through the use of this tool, students experience power and autonomy in the classroom as they track and measure their learning growth. Goal setting is the number one high-impact teaching strategy for student learning. My classroom’s bump-it-up wall establishes differentiated and challenging goals for my students. They can track their progress and identify where they might need help. We use student-teacher conferences for students to evaluate their own learning. Students also provide evidence to show when they’ve achieved a goal. Through the use of this tool, feedback is authentic and purposeful because students understand the purpose of their learning tasks. BUMP-IT-UP IN MATHTo create a math bump-it-up wall, I first administered a counting preassessment. I aligned the results to the various curriculum levels. I then created five leveled examples with annotations that demonstrated counting achievements and possible goals to progress students’ counting abilities. For example: The first level demonstrated the ability to count forward and backward by ones. The next level showed skip counting by twos, fives, and 10s. Each level was a little more challenging, and the fifth level asked students to be able to identify the rule for any counting pattern and complete patterns that had missing numbers. I took time to confer with each student, showing them their test papers and helping them to identify their strengths and stretches. They placed their name under the example that best described what they could currently do. They studied the adjacent annotated example to see what they needed to do to progress to the next level. Throughout the unit, I conferred with my students regularly, and they came to me with their work when they thought they were ready to move to the next level. The levels of the bump-it-up wall became my differentiated success criteria for assessing student progress in the counting unit. This directly informed my teaching and the tasks I provided to students. It further created student agency opportunities by giving students the choice of which level of activity they wanted to work on in each lesson. BUMP-IT-UP IN WRITINGAfter my success with using this tool to set goals in mathematics, I created a new bump-it-up wall for writing. I chose the 10-week term when we were focusing on narrative and persuasive writing genres. I quickly came to realize the necessity of narrow and specific goals, since there were so many aspects of writing that could be analyzed and scrutinized. I knew that it would take considerable time to progress in writing and that a whole term would be needed for students to see some progress. I selected the “ideas trait,” as identified in Ruth Culham’s book 6 + 1 Traits of Writing, as the focus for the bump-it-up writing wall. Using Culham’s book, I found example writing pieces and attempted to annotate these pieces in student-friendly language. As I conferred with my students about their own writing, I soon realized that the pieces on the bump-it-up wall showed a logical progression of ideas. However, the annotations were not accessible or easy to apply to the students’ own writing. I adapted my approach and worked with the students to create annotations that made sense to them. We looked at each writing piece over a series of days, and together we discussed what we liked or didn’t like about each piece. The students told me what they noticed about each piece and what they wished to see more of. As the facilitator of this activity, I was careful to keep them on course with “ideas” as their analyzing lens. This process proved to be much more effective, and students were able to evaluate their own work and set themselves goals using the wall. The strategic use of a bump-it-up wall has been a success in my classroom. Not only can I accurately report student progress back to parents, but students themselves are able to understand and discuss their progress. It also has made goal setting a much more authentic experience for my students, which has increased their motivation to challenge themselves.

0 Comments

Published on Edutopia: www.edutopia.org/article/3-ways-get-young-students-excited-about-revising-their-writing April 25th, 2022

When I used to ask my students to revise or edit their writing (and I was mistaken back then to believe those were the same thing), the response was either a groan or a glazing over of the eyes. My students felt nervous about and resisted editing because they didn’t know how to make their work better. I had no tools to teach what I now understand to be the meatiest components of the writing process. Through research and professional development, I came to understand that although different researchers have slight variations on the essential phases of writing, key elements were consistent in every literacy expert’s model. Jennifer Serravallo, for instance, describes the writing process in The Writing Strategies Book as follows: generating and collecting ideas, choosing an idea, rehearsing (talk or sketch), drafting, revising, editing, and finally publishing. Ruth Culham recommends similar steps in 6 + 1 Traits of Writing, describing the process as prewriting, drafting, sharing, revising, editing, and publishing. After studying these models, I realized I wasn’t distinguishing between revising and editing. Editing is in fact all about improving how writing looks, whereas revising is all about improving how writing sounds. This means that when we edit, we look at spelling and punctuation. When we revise, we look at organization, sentence fluency, and word choice. It’s the revision element that students ultimately didn’t understand. I also wasn't giving my students enough opportunity to publish their work, which made the revision and editing process feel redundant and inauthentic. Here are three ways I transformed how I taught the revision process. 1. FOCUS ON WRITING TRAITSStudents don’t know where to start with revision, so it is imperative that educators break the revision phase into small achievable chunks. To do this, I use Douglas Fisher and Nancy Frey’s gradual release of responsibility (GRR) instructional framework. This approach is never more useful than when teaching students to revise their writing. First and foremost, to break the onerous task of revision into more manageable chunks, the teacher should identify a writing trait to focus on. Culham identifies ideas, organization, voice, word choice, and sentence fluency as “revision traits.” Narrowing the focus to one of these when teaching students to revise is essential in helping them to succeed. 2. MODEL THE WRITING PROCESSIn my year 2/3 class (second- and third-grade students in the United States), I chose to focus on the ideas trait. We had already spent considerable time brainstorming ideas for narrative writing, and my students had many possibilities for writing a narrative piece. Following John Hattie’s high impact teaching strategies (HITS) of explicit teaching, I modeled a narrative that lacked depth. I took a simple student text and simplified it even further. I wrote the bare bones of the story, ensuring that the organization was correct (introduction of characters, problem, resolution, and ending), but the nouns were plain and there were no adjectives or detail. In the past, if a student had presented such a story, I would have accepted it, knowing that they’d followed a narrative structure. In my mind, I would have thought it was boring, but I had no tools to provide feedback to help them improve. Now with my knowledge of the writing traits and the phases of writing, I was ready to help my students expand on their ideas. I began with the introduction of my modeled story and pointed out to my students that although I had a main character identified, they knew nothing about her personality or the setting of the story. I used sticky notes and the think-aloud strategy to show my students how I would change parts of my sentences, or even add in sentences that gave my character more depth or led my readers to understand the setting. I was showing my students that a messy first draft was normal. The next paragraph was also basic, and now it was time to move into the “we do” part of the GRR model. I read the paragraph aloud and asked for the students’ input into what details might be missing. With their questions about where and what was happening, I again modeled inserting and exchanging words to give more depth to the story. We also used sticky notes to add entire sentences. By now the students were very engaged. Then it was time to hand over the reins. I asked my students to go back to their tables with a partner and read their introductory paragraph to each other. They worked together to improve just this one paragraph with sticky notes and colored pencils at their disposal. Riss Leung of the Oz Lit Teacher blog says “progress not perfection,” so I was extremely satisfied to see that each student had been successful in making at least one small change to improve their writing piece. 3. HOLD WRITING CONFERENCESAlongside the HITS of explicit teaching and worked examples, feedback through writing conferences was another invaluable tool that helped my students get over the line from feeling overwhelmed and uninspired to excited and knowledgeable about the revision phase. During the one-to-one writing conferences, I read their story with them, using an admiring lens to praise them for anything that worked well or sounded good. I chose one point that could improve the story and coach them through revising this one point. For example, I asked one student, “As the reader, I wish I knew more about this resolution. Can you add more about the adventure your character had at this point in the story?” Now when I ask my students how they feel about revising their writing, I rejoice to hear that they feel confident to reread their writing and proud that they have created something interesting. With carefully planned lessons, revising writing can be engaging and rewarding for both the teacher and the students. It means that students are ready and confident to publish their work, and we can all be satisfied that their published pieces demonstrate progress from their first drafts. A teaching focus to lift students' writing- Helping young writers improve with a unit on word choice16/1/2022 Published at Edutopia on Jan 12th 2022

www.edutopia.org/article/helping-young-writers-improve-unit-word-choice For a beginning writer, organization and conventions are mammoth mountains to climb and they can fill all of our instruction and feedback time. But what about those proficient writers who have already mastered these things? According to the standardized state-wide writing assessment (NAPLAN), my school had relatively high scoring students but they were not showing much growth between years. How do we help these high achieving writers who already have a great grasp on conventions and organization achieve greater growth as they progress through primary school? Combining insights from literacy consultant Narissa Leung’s Oz Lit Teacher Blog, Ruth Culham’s 6 + 1 Traits of Writing, and Jennifer Serravallo’s The Writing Strategies Book as well as our professional development, I worked with my fellow second and third grade teachers to develop some ideas. Setting Goals We agreed that each teacher would zone in on precise and engaging verbs as a small crumb to focus on when teaching writing. Although all students within the class would be included in the instruction, the aim was to improve our top writers’ word choices and see them making direct revision changes in their writing. We would give ourselves six weeks, using Hattie’s High Impact Teaching Strategies ‘Explicit instruction’, ‘Multiple exposures’ and ‘Feedback’ to achieve our goals. We were aware that word choice as a focus for revision was new for our students and it would be essential that mini lessons explicitly explained and modelled this process. This would need to occur regularly and we would narrow our feedback explicitly to demonstrate the importance of this skill. Modelling Word Choice The explicit instruction included the use of mentor texts that showed interesting and unique verbs to communicate a message. I talked to my students about creating an image in the reader’s mind. We discussed synonyms for different verbs that could alter and tweak a visualisation. Some of these mentor texts and phrases included: Tilly by Jane Godwin ‘it rolled cool against her skin’ and ‘she arranged them on her bed’. Possum Magic by Mem Fox ‘She made dingoes smile and emus shrink’ and ‘she could be squashed by koalas’. As we began to implement our new approach we were thrown back into lockdown and remote learning. I was determined to keep my students engaged in this writing focus even if we were working from home, using online resources like GetEpic to gather mentor texts. For example, I selected a text called ‘Boogie Bass, Sign Language Star’ by Claudia Mills. I conducted a quick formative assessment to ensure the students knew what nouns, adjectives, adverbs and verbs were; clarifying any confusions as we went. Then we read some of the text, enjoying and searching for the words and phrases that created specific images in our minds. After this, I adapted the beginning of a picture story book by rewriting it with the most simple of word choices. In a small group, the students contributed ideas to improve the story by adding and changing words. Throughout the process, I encouraged students to consider whether the new words were the best or whether we were inadvertently making the piece sound repetitive. The students were hooked to the discussion and were excited to continue the story on their own. I didn’t show the students the original text to avoid them feeling like there was a right or a wrong way to progress the story. I only wanted them to see that there were choices and that they didn’t need to stick with their first, second or even third choice if they didn’t want to. When we were allowed to return to school, I introduced an adapted version of a Frayer chart. This was presented in an enlarged format with the whole class and we could model our thinking around these new verbs. In addition, I explicitly taught and actively modelled how to spend time revising writing with a focus on word choice. Students were also encouraged to write more than one draft with the attitude that the first draft would never be the best. After writing a piece, I modeled and instructed students to take a highlighter to their work and identify the action verbs within the piece. I pointed out how different verbs could truly give the reader a different impression of what was going on or a different understanding of the character’s personality. Phrases such as ‘We have to go!’ She shouted, compared with ‘We have to go, she whispered,’ completely changed the mood in a story. The students would then spend time brainstorming synonyms or alternative phrases to create a clearer or different picture in the reader’s mind. Monitoring Student Progress It became apparent over the course of the unit that students were becoming much more interested in revising their writing with a view to improving it. They were selecting their words carefully and making changes when they re-read their work. Something that I didn’t expect to see, was the development in my most struggling writers. Even though for these students, handwriting, spelling and ideas were often a challenge, gradually they were making changes based on the consideration of which words would convey their message best. Not only did this Word Choice unit develop my students’ ability to revise their writing carefully, it also lifted their enthusiasm for writing. Written by Joanna Marsh ‘Writers learn to write from studying the craft of other writers’ (Fountas & Pinnell, 2017, pg 225 When my students are excited about writing, I am excited about teaching! Or is it the other way around? Certainly a chicken versus egg conundrum, nevertheless, this is a story about engaging our youth in creative writing. Like many writers, our students’ work is deeply influenced by their exposure to the books they have read (or had read to them). (Laminack, 2007) ‘Choose your Own Adventure’ writing project Let me take you back to a time in my career when I was a Year 4 teacher at what I would describe as a challenging school. I came to be these students’ teacher midway into Term 2, 2015 and they would have to be the most challenging group of children that I have taught in my 15 years of teaching. I learnt a lot about engaging the disengaged that year, but I would like to describe to you, one project that I developed to engage these students in writing. I’d recently bought a box set of ‘Choose your Own Adventure’ books (Choose your own adventure- Race Forever, 2005, Scholastic). I was struggling to get some of my students involved in reading and writing. I showed them the books, but the covers are old fashioned and the students didn’t really take to them. I tried again. This time I began reading the books to the class. I pointed out the unusual style of second person writing and let the class cast votes as to the direction each story would take. Offering choice was the hook. After reading these to the class for a few weeks, the students began wanting to read the books independently, which was very exciting. It occurred to me then that perhaps I could transfer this engagement to a writing project. We’d only just completed a unit on narrative writing, where I’d taught the students about planning, setting, characters, problem and resolution. They were in the right mindset for this task. I proposed my idea and stuck up a huge piece of butcher’s paper. We began by brainstorming a problem. What would Year 4 students consider an exciting problem? Well it was getting close to Christmas and being the very politically minded young people that they were, they decided that the story would be about the Prime Minister cancelling Christmas. ‘Okay’ I said, ‘fair enough, but you have to think about why.’ I explained to them that the story wouldn’t make sense without a reason for this devastating problem to occur. We collaborated some more and they were able to agree on a reason. We were ready to plan. We used a tree diagram and began with an idea. From there I drew two branches. These would be our first two choices. From each of these two choices I drew two more branches. Now we had four possible paths for the reader to take. My aim was to ensure that each student in my class would have one part of the story to write. So the planning did not continue on a pattern of doubling as you may imagine. Some of the parts at this point led straight to a conclusion, whereas other ideas circled back to a part on another path. It may sound confusing but when you map it out and have 20-something eager helpers, it will be okay. We’d worked out five different endings in total and ensured that every path led to one of these. There were enough parts so that each student was responsible for writing a page and each had an assigned number that would be the actual page number. We spent significant time analysing the style of the book. I had to reiterate and model how to write in the second person and present tense, explaining that we would be placing the reader as the main character. It was also imperative that students understood that they could write plenty of detail for their part but they could not write anything new. It had to follow the class plan. As in any class, there were students who were ready to go and others who felt unsure. I was able to work with those that were unsure together in a group to unpack their parts a little more and give them more of a framework for what to write. The students wrote their parts. Some wrote a page, some wrote a paragraph. It didn’t matter as long as they covered the information they needed to, within their part. I helped each student proof read and edit their work, to ensure that they had been successful with the present tense, second person criteria. I collected all of their drafts and put them in the order they needed to go. I had already typed up the little choice boxes that were to appear at the bottom of their pages (the big map we’d made, travelled to and from school a number of times) and I attached these to the drafts. We read the drafts together as a class and identified any areas in the story where there was repetition between two pages or something clunky that didn’t make sense. Due to the mini lessons and proofing process, there really wasn’t too much that needed to be changed or fixed. The next step was the final copy. Students took their edited drafts and rewrote their page as neatly as they could. They then illustrated their work on a separate piece of paper. All that was left, was for me to collate the work, add the choice tags at the bottom and photocopy the book for each child. Their reaction when I handed them the completed book was priceless. Never before had I seen them so excited about their own work or so proud. It was exactly what I had been hoping for. Testing the project again A few years later I changed schools. The cohort at my new school was quite different. I was working with Year 3s this time and I decided to give the project another go. I’d learned from my mistakes (e.g. leave a margin so that it is easier to staple the book together) and felt a lot more confident as we broached the planning stage. I showed them the book that my previous students had made and the response was enthusiasm and excitement. They all wanted to be a part of this project. Again, this was the perfect project to end the year with and these students also chose a Christmas theme (see Figure 1 and 2). I had 100% buy-in and the end result was just as precious. How can we apply this to other age groups? In 2020 I had a Year 2 class. The ‘Choose your own adventure’ books sat for a while in the classroom library, untouched. I saw some of my capable readers losing engagement in their reading and decided it was time to introduce the joy of mystery and choice. I worked with them in a small group, showing them how the books worked and guided them through reading some of them. Once again, the modelling hooked them and they began to read these books independently. I then read some to the whole class, engaging everyone in making choices about the paths we should take as a group. We began a unit on narrative writing. With this age group I was not prepared to task them with writing such a complex story, but that didn’t stop me from modelling it. I presented the students with the first page of a story I’d titled, ‘The Missing Whiteboard’. It included the children from the class, as well as me, their teacher, and it had two choices at the end of each page. The class voted, we ticked the box and then they had to wait a week for the next instalment (see Figure 3). Like many classes in 2020, our regular way of teaching and learning was challenged when we were all subjected to a range of Covid19 restrictions. The story was only midway through! We didn’t let that stop us though. During the seven week remote learning phase, I emailed the class a new instalment of the story each week. We would then meet together on WebEx and continue to vote on the path the story would take. It was a fabulous way to keep the students engaged while learning from home. I even had one student who decided to write her own ‘Choose your own adventure’ story. She asked her family to vote on the path that it would take and enjoyed hearing suggestions from the rest of the class about where she could take the story next. Conclusion Why is engagement in writing so important? Because it connects our children with the joy of reading. Writing creatively helps the student to become a critical reader and this is what we want for our students. It contributes to the expansion of their vocabulary, grammar and knowledge of structure. ‘Real writers are eager for collaboration.’ Mem Fox (Mem Fox, 2016) Working collaboratively to represent each voice and create a collective, cohesive text is no easy feat but definitely one worth pursuing. Through the use of mentor texts and the gradual release of responsibility, students of many ages and abilities can experience success through a ‘Choose your Own Adventure’ writing project. Joanna Marsh Year 2 Coordinator and teacher Woodend Primary School References Fountas, I.C., & Pinnell, G.S. (2017). The Fountas & Pinnell literacy continuum. Melbourne: Pearson Australia Fox, M. (2016). Should we teach writing well or badly?: The Donald Graves Memorial Speech. Australian Literacy Educators’ convention, July 2012. Retrieved from https://memfox.com/for-teachers/should-we-teach-writing-well-or-badly/ Laminack, L.L. (2007). Cracking open the author’s craft. New York: Scholastic Leung, N. (February, 2020). 5 teacher tips for overcoming “I don’t know what to write about”. Retrieved from https://www.ozlitteacher.com.au/2020/02/02/teacher-tips-for-overcoming-i-dont-know-what-to-write-about/ Montgomery, R.A. (2005). ‘Choose your own adventure’ series. Retrieved from https://www.cyoa.com/ Read.Think.Explore Are you interested in trying this in your class? Start small with these easy steps:

As students line up for a pump of hand sanitiser, there is a palpable excitement. But there is also apprehension, and not just from the students. Both teachers and students have been away from face to face teaching and learning for so long. As many parents know, the energy needed to keep children engaged in learning for six hours is no mean feat. So there will be an adjustment phase needed. The teachers are more than aware of this. They have missed their students, they have missed teaching the way they were trained to teach! And they know that students have missed them too. But there was a luxury in rolling out of bed and straight to a desk.

On the first day back at school, students are bubbling with enthusiasm. They can’t wait to see their friends and teachers. There will be a moment, an hour or a day, when the reality sets in and they realise that school goes until 3:30pm for five days a week. No longer can they take their 25 minute recess break that ends up going for an hour and a half because the adults need some space to think and work. It will be a new challenge, to transition back to school. The teachers know this. They have reached back into the depths of all their training and pulled out every engagement trick in the book. They have a sleuth of ‘Brain breaks’ up their sleeves and a heart full of compassion and understanding. They are ready. Published in The New Woodend Star- October 2020 edition https://issuu.com/newwoodendstar/docs/nws_october_2020 Despite the fact that the word “dictation” has negative connotations, I’ve found that the practice itself has benefits. Not only does dictation promote the learning of spelling in context (which is much better than the old-fashioned and not-so-useful method of rote learning), it also promotes the learning of correct sentence structure and punctuation. Plus, I hear whoops of excitement as I conduct my weekly dictation with my students!

Dictation can be a useful practice for many grade levels and subject areas. When I first started teaching 13 years ago, I used dictation with English Language Learners to develop their listening and writing skills, and later I used it with teenagers during mainstream English classes. (If you’re a secondary teacher, I’d highly recommend learning about the dictogloss activity, which helps students reconstruct dictated texts. The process of a dictogloss is to read a text of relevance and ask students to record as much as they can while you read. They need to listen for the important points. The next step is for students to join forces. They partner up and combine their notes to create a more comprehensive summary. The pairs can then join another pair to create an even more in-depth summary.) Here, though, I will explain how I engage younger students in dictation. Every week I give my students a focus phoneme to explore, analyze, and practice. I provide them with a list of words that contain that phoneme, color-coded to represent beginner, medium and advanced words. They discover different graphemes for that phoneme and select a few words (the number will depend on the ability or age of the student) to analyze in more depth. There are a number of activities that I use to help students segment their chosen words into phonemes and graphemes. We also play a version of Celebrity Heads where a word from the class list needs to be guessed. Students use a chart and ask questions about the phonemes and graphemes within the word to help them guess the correct word. At the end of the week, I conduct my dictation. Depending on the age group I’m teaching, I use different rubrics and ways to provide feedback. At the third and fourth grade level, I provide my students with a three-level rubric they can use to assess their work. At the first and second grade level, I talk the students through an easier scoring system or print out a very basic three-level rubric. Here’s how I currently conduct dictation with first and second graders: I construct three sentences. Each sentence includes three words from the list of words with the focus phoneme, and each sentence increases in spelling complexity. Each sentence also includes as many high frequency words as possible. I read the first sentence fluently and with expression once, and then in smaller parts as many times as is necessary for all students to write it down. Once students have written the first sentence, I ask them to swap their normal pencil for a red one and get ready to correct their work. It is important to note that I do not collect their scores—therefore, students soon learn that there’s no need to cheat as they correct their work. I write the sentence clearly on the board and then get my red marker. I announce that students may give themselves a tick if they remembered the capital letter at the beginning of the sentence. (Cue first whoops of success from students! Also, if they didn’t remember the capital letter this first time, it is highly likely that they will remember it for the next sentence.) I then ask students to give themselves a tick for the period at the end. There are occasions when the sentence will call for an exclamation or question mark, and we discuss and celebrate when students get this correct. I then underline the three words that have our focus phoneme. I reward my students with a tick if they write the correct grapheme for the focus phoneme, even if they haven’t spelled the whole word correctly. For instance, I might say, “Give yourself a tick if you used a ‘kn’ in the word knock.” An alternative process would be to assign students with specific words to practice and analyze at the beginning of the week (rather than let them choose). In this instance, it would be appropriate to expect that the entire word is spelled correctly rather than only the focus phoneme. I then select a bonus word (one of our high frequency words) and award a tick if students have spelled this correctly too. For instance, I might say, “The bonus word is ‘she’—give yourself a tick if you have spelled ‘she’ S-H-E.” The students then give themselves a score out of 6 for this sentence and we move on to the more challenging sentence. There is no need for me to collect the scores from this weekly test as they do not inform my teaching of the next week’s lessons. (I have a separate diagnostic and summative spelling test that I do once a term for this purpose.) I see the greatest value of this lesson in the immediate feedback it provides to students in a fun and non-stressful environment. http://theconversation.com/learning-by-rote-why-australia-should-not-follow-the-asian-model-of-education-5698 https://www.theeducatoronline.com/k12/news/education-expert-slams-australias-tolerance-of-failure/242171 Article featured in Edutopia: https://www.edutopia.org/article/how-use-dictation-spelling-instruction |

AuthorSometimes I want to say stuff about education. Here are my articles. Archives

April 2021

Categories |

Photo used under Creative Commons from homegets.com

RSS Feed

RSS Feed